Three Reasons Rent Growth Will Slow in 2024

Rent values rose for the 35th consecutive month nationally in July.

However, monthly rent growth has eased during the past four months. In regional Australia, rent value growth has been slowing since April last year, and rents are close to flattening out (albeit at high levels).

Slowing rent growth is expected to be one of the key housing market trends next year, for several reasons.

Firstly, the cash rate is expected to fall, which could increase investment and first home buyer activity.

Secondly, income growth is expected to slow, which might prompt a change in housing preferences.

Lastly, stretched rental affordability could see movements to more affordable areas, and base effects mean there will be a limit to how high growth can go. These factors are unpacked in more detail below.

1. Rents move with interest rates, and interest rates could be on the way down next year

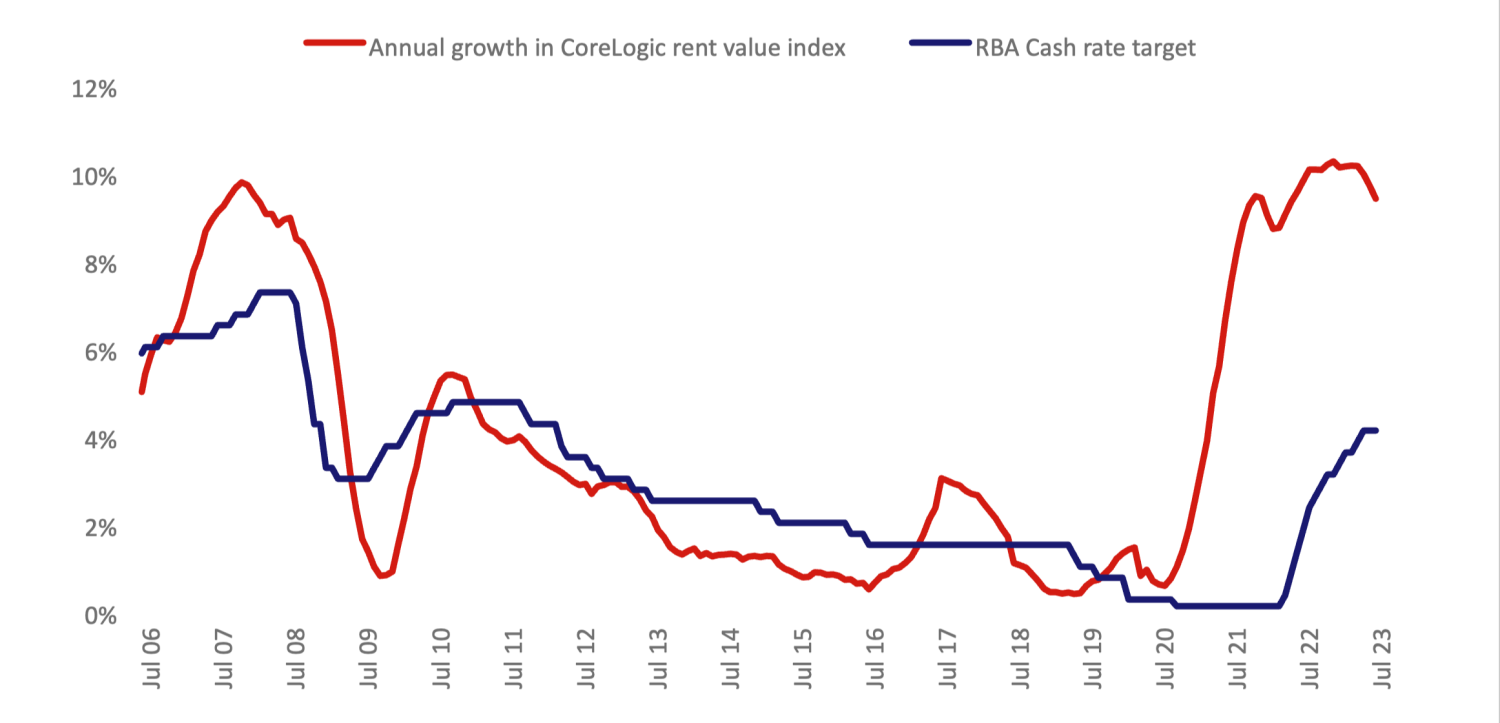

Annual growth in rent values and interest rates move together over time. Figure 1 shows rolling annual growth in the CoreLogic rent value index against the RBA cash rate target.

RBA cash rate target and rent growth

In 2024, each of the major banks is now forecasting a decline in the cash rate. A reduction in interest rates could increase demand from housing investors, and increased investment purchases add to rental supply, which may serve to lower rent growth.

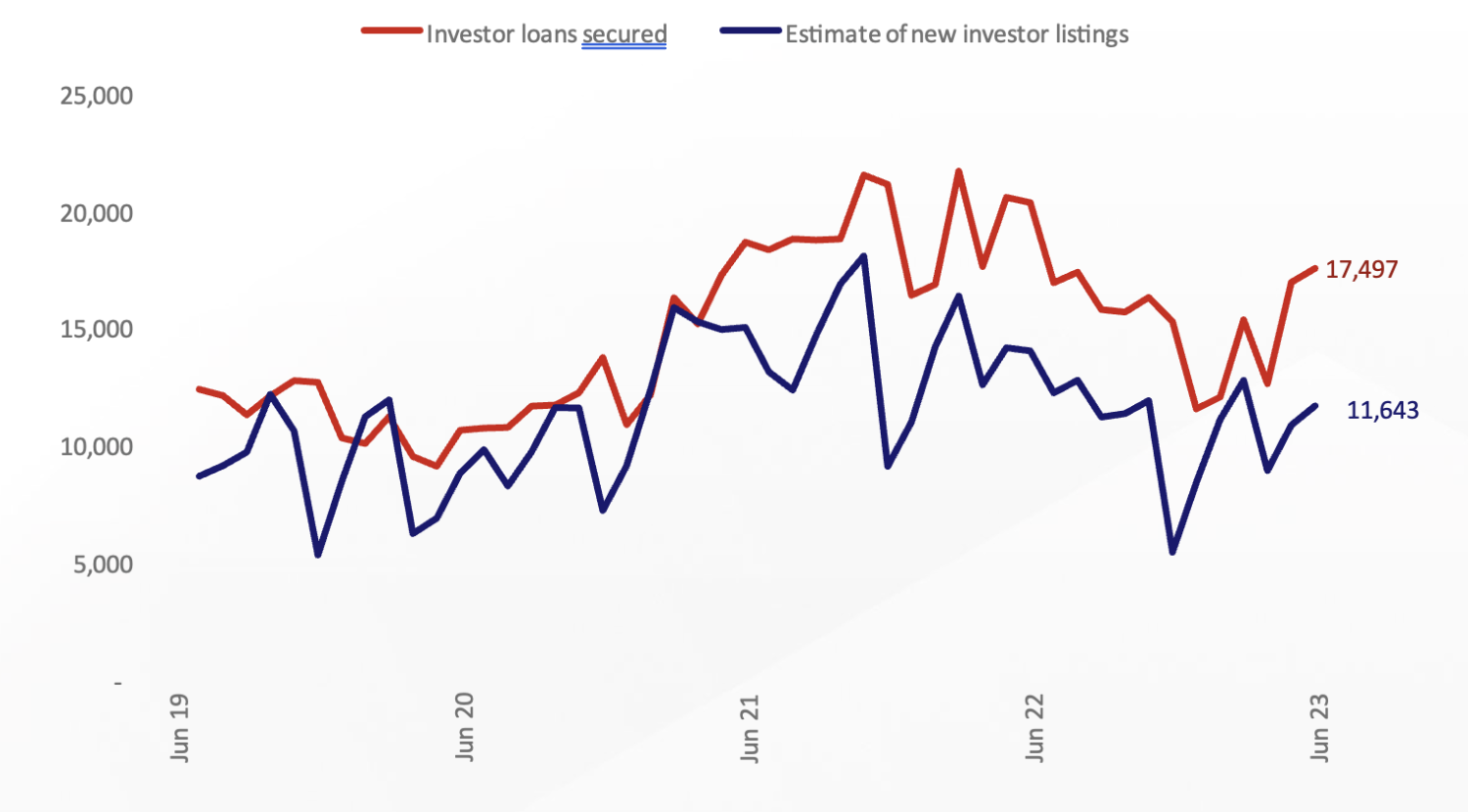

Expectations that the RBA will be done with rate hikes in 2023 may even be contributing to an early recovery in investment activity. Figure 2 shows the rise in new investment loans secured since the start of the year. Investment loans are offsetting the rate at which new investment listings are being added to the market.

Number of investor housing loans secured versus properties listed

2. Softer income growth could lead to a change in housing preferences

Household income growth shifted higher through the pandemic. Initially income growth was supported by the largest peacetime fiscal stimulus package on record, and later, tight labour market conditions supported wages growth. ABS measures of total gross household income in the national accounts has averaged 1.4 per cent per quarter since the start of the pandemic, almost double the growth rate in the five years prior (0.8 per cent).

Income growth is likely one of several factors that contributed to the break-up of share-houses through the pandemic. People could afford leases on more spacious properties, which has contributed to lower stock levels as households spread out across the dwelling market.

However, income growth could be another metric that slows next year. Monetary policy is taking effect in reducing demand in the economy, the unemployment rate rose to 3.7 per cent through July, and annual growth in the WPI slowed to 3.63 per cent in the latest print.

As income growth slows, renting households may look to adjust their housing situation, and re-form share houses.

In regional Australia, the average household size has returned to pre-pandemic levels, and is starting to rise across the combined capital cities.

3. Rental affordability is becoming stretched

High growth in rent values has seen an increase in the share of income required to service new rents, which was estimated to be 30.8 per cent nationally at March 2023 (the highest level since June 2014). CoreLogic’s measure of rents have increased 29.3 per cent since a low in August 2020, or the equivalent of a rise in median weekly rents of $134.

Rent value growth is likely to slow because of base effects alone, but renters also tend to be on lower incomes, which means there could be a ceiling on how high rents can go before tenants adjust their housing preferences. As noted in the previous section, this can look like more share-housing.

It could also be showing up in internal migration patterns. In the 12 months to June last year, ABS data showed more affordable rental markets like Logan—Beaudesert and Ipswich with the first and third highest volume of net internal migration across the country.

This overtook the Gold Coast, which had the highest net internal migration in the previous year. Such internal movements could ease demand in the most expensive rental markets, bringing down growth in the national rents.

Most markets now seeing a slowdown in growth, some rent falls

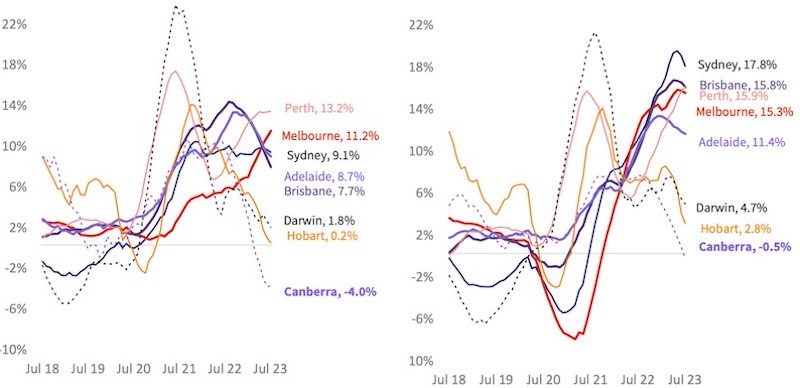

Figure 3 shows rolling annual growth in house and unit markets across the capital cities. Most rental markets are now seeing growth flatten out, or moving lower. Canberra rents are firmly in decline, and Hobart house rents look as though they will soon follow.

Annual change in house and unit rents

Rent values also fell in the 12 months to July across a handful of SA4 markets, including the South East of Tasmania (down 4.5 per cent), the Southern Highlands and Shoalhaven (down 3.8 per cent), and the Capital Region of NSW (down 1.3 per cent).

Just because rent growth slows, doesn’t mean we should lose sight of reform

Importantly, although we are likely to see a further slowdown in the pace of rent increases, rental affordability challenges are likely to persist.

On top of cyclical factors driving a slowdown in rent growth, more can be done to ease rental values and make renting better.

The recent national cabinet proposals for housing are a great start. The ambitious goal of 1.2 million well-located homes to be built in the next five years would help to bring rents down.

Minimum standards around the quality of rentals is also a positive step for improving the nature of the tenure.

The provision of more social and affordable housing can also help to protect lower income households from the extreme fluctuations in rental values seen in the past few years.