Housing Unaffordability, The McMansion Legacy: Is The Solution Getting Naked And Sharing Toilets?

TUD+ MEMBER CONTENTBy Chris Isles, Executive Director of Planning, Place Design Group

Housing affordability is currently a topic that all levels of government are talking about (and some are even doing something about it... or at least trying).

However, if I have to read another ‘Top 10 Most Affordable Suburbs’ article in the paper, I will go crazy.

There are lots of theories and policy ideas being thrown about. Things such as ‘removing negative gearing for investment properties, to increasing land supply’, or ‘providing capital gains tax incentives for baby boomers to downsize’. We could even track back to expanding the tried and tested ‘First Home Buyer Incentive programs’. Which according to leaks about the upcoming budget seems to have been reinvented this time via tax concessions.

Whilst time will tell which (if any) of these will actually prove effective in improving or delivering affordability in housing, what I am not seeing is proper discussion around the assumption of what ‘housing affordability’ really is.

I’m not talking about how you might quantify ‘affordable’, although that is a worthy discussion for another day. Nor am I talking about product types or the ‘missing middle’, although that too is another good one for healthy debate.

What I am talking about is ultimately our underlying assumption or predisposition to what our minimum expectations are when it comes to the ‘housing’ we consider to be the minimum we will (or are prepared to) live in and therefore really the benchmark for housing that sets the affordability price point, or more aptly the ‘unaffordability’ price point.

Last week on a flight to Sydney, I was flicking through the Qantas inflight entertainment system and stumbled upon the ABC documentary series by Tim Ross, Streets of your Town.

A very well put together look at issues of architecture, identity and housing excesses here in Australia. Tim has a personally shared penchant for all things ‘Modernism’, so I found it a real pleasure to watch. However, some of the underlying and key points made in the series mirrored my current crusade to explore the issues of the housing diversity and affordability.

And, the consequential tensions that appear between communities over how and where we will fit everyone as we grow.

One of the observations that Tim made was a link between the McMansion era we have experienced, and a loss of architectural and design identity within Australia. This is something that really resonated with me. Tim made an observation that his Grandparents grew up in a house with seven people and they had one toilet in the backyard.

Whilst his parents grew up in a house with five people with one toilet inside and yet our generation are growing up in houses often with more toilets than people. As an indicator of excess and loss of our way, I think this is a pretty telling indicator.

But if we create a ‘toilet indicator’ and use this as a measure of housing affordability and size, I am sure we will find a link to many of the issues facing us in infill Australia?Go with me. How can we possibly deliver small affordable housing, or even dare I say it, small affordable infill housing such as ‘granny flats’, secondary dwellings, terrace housing and the like if we feel a need to have a toilet for every person in the house. There is a reason that the 80sqm terraces worked in Sydney for decades and it was certainly not because they had three toilets in them.

It’s actually ironic that we are sitting on our 600+ sqm blocks, with residents (and Council’s for that matter) actively resisting and stopping the delivery - or even preventing the discussion - of secondary dwellings and smaller houses in our existing suburbs, YET we have so much evidence that we can fit those dwellings in less than 50sqm. Yes, they might only have one toilet, but surely we should be putting housing affordability issues over and above a higher ‘toilets per square metre of house’ indicator scale.

And so, our cities are facing a massive divide.

Some of us are squeezing into smaller apartments or townhouses while others are enjoying a great big sprawl in an over-sized home with empty bedrooms and unused bathrooms, and a high ‘toilets per person’ ratio. Yet we still complain we have affordability issues.

Back to Tim. Picking up on his line of thinking, when our grandparents had themselves and five kids all in a house, probably with two bedrooms, a kitchen and a living space, I am sure affordability was an issue then as well. The difference being that people likely bought or built what they could afford.

The house would have had bare floor boards, no wall linings and certainly limited decorations and embellishments. But it was a roof and four walls and you had time to improve and upgrade the house when you could, or expand it as your family grew. But in the ‘now’ era where we have to have it perfect from day #1, we are buying houses with four bedrooms, dual living for the kids and two cars - even though we don’t yet have kids - but we will, and they will need ‘their space’.

So, if we go back to basics and Mr Maslow and his hierarchy of needs, I am confident his hierarchy just spoke about ‘shelter’ being one of the critical elements of the physiological category in his hierarchy. It is worth noting this is the biggest need we have as well.

However, I don’t recall the physiological need for shelter stipulating the minimum number of bedrooms or bathrooms. So it begs the question: Do we need internal walls, a nice kitchen with laminate benches and that bathroom tile featured on the 2016 Block Sky High series that was so fashionable? Or are four walls and a roof enough to satisfy our basic shelter requirements?This is the exact question or proposition that London’s Mayor, Sadiq Khan, is asking London residents to consider.

And I think it is a worthy discussion to open up here in Australia as well.

Khan has adopted a policy to subsidise a new generation of ultra-basic “naked” homes that he believes will sell for up to 40% less than standard new builds.

But there is a catch.

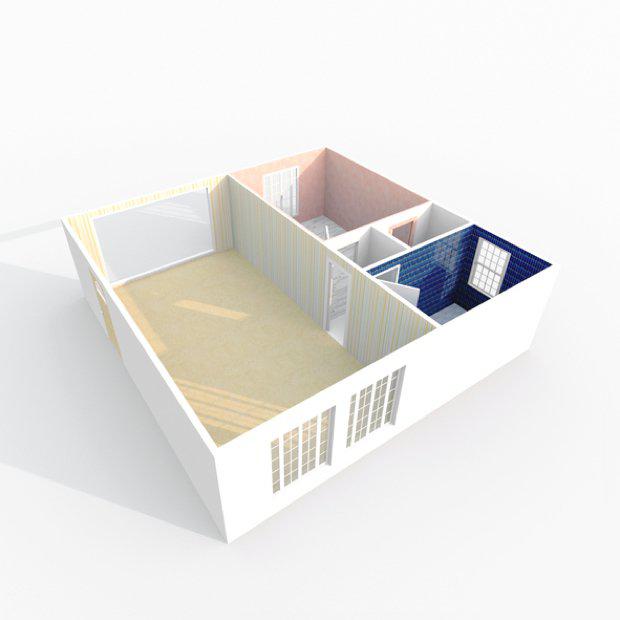

The ‘Naked House’ unit will be nothing more than a well-designed shell. The houses will have no partition walls, no flooring nor wall finishes. They will only have basic plumbing and absolutely no decoration. The only recognisable part of a kitchen will be a sink.

A 'naked house' render. Courtesy NakedHouse.

The houses will initially be 50sqm of open plan dwelling, however, the floor area of the house can be easily expanded in two ways: through a rear extension or by infilling the double height space within the envelope.

If a resident wants more room without extending the envelope of the building, they can build out from the mezzanine provided to form a two storey house. To make this process as simple and accessible as possible, an internal concrete shelf protrudes from the blockwork walls around the perimeter. Residents can then easily support timber joists (and their desired floor build-up) from this shelf to form a new floor.

In my opinion these are all super clever design tricks that show it is possible to design for efficient and affordable adaptation.

But if this basic shell of a house, with room and ability for adaptation and embellishment over time can be bought for 40% less than a larger and fully finished cousin, I can’t help but think we should be considering this type of product here as well.

The cost of land, which is often the dominating line item in the final price for these project, could be removed in favour of a leasehold arrangement over public land.

Rather than incur hefty charges right off the mark (and charged to the buyer), this means that occupants will pay a “monthly ground rent” to the local authority who owns the land. And to ensure that the Naked House units "remain affordable in perpetuity," the developers could have a resale covenant in the lease which “locks in the original discount for subsequent purchasers”.

To me, using crown land in this manner is as revolutionary as the naked houses themselves.

It’s also a concept worthy of further investigation by us here in Australia.

Because if the discussion here is purely one of affordability, then these would be great options and tick basic housing needs and maybe time for current generations to talk with their grandparents about how it is possible to buy a basic house that matches both your needs and ability, with ‘wants’ not even in the discussion, then maybe we can provide entry points into the market. The problem at the moment is that the entry point is too high, both in terms of price and in terms of the housing being built.

Interestingly though and perhaps predictably, this plan is facing stiff opposition from Khan opponents, as I am sure it would here in Australia too, with our rampant NIMBY syndrome.

Andrew Boff, chair of the housing committee, and opponent to Khan said, “this is not the right trajectory for how we develop housing. These don’t look to me to be designed for growing families. They are for singletons and couples. They need homes as well, but if we don’t build larger properties for families we are creating a time bomb in London. There are over 300,000 children growing up in overcrowded conditions and that number is rising.”

This too is illustrative of a key problem that we equally face here in Australia. Politicians making decisions for our communities based on their own values, expectations and social norms, and assuming that because they wouldn’t want to live in a ‘naked’ house, no one else would.

But the acceptance of this type or housing here will ultimately come down to current and future generations being willing to accept a lower ‘toilet rating’ index housing and see us getting back to building housing that is benchmarked off what people can affordable, as opposed to continuing to build the same bigger housing of a decade ago and then wondering why it is unaffordable.

So what are the takeaways?

It’s time for us to re-look at our expectations for housing and to ‘cut our cloth to suit our budgets’ - and perhaps build smaller and more basic housing options.

It’s time to get naked and not be ashamed of it.

Innovation in leasehold options particularly over crown land is worth exploring for Australia.

The ‘toilet ratio’ affordability index is a thing. Copyright pending.

As Executive Director for Planning at Place Design Group, Chris Isles leads Urban Planning teams internationally in Australia, China and South East Asia.

A trusted advisor to the Australian government at all levels and private developers alike, Chris’s focus is guided by the global imperative for the planning profession to respond, and keep ahead of the global urbanisation trend to ensure that the future of cities for people is not lost during rapid urbanisation.

Chris was awarded Australian Planner of the Year for 2015 and is a member of the Queensland Urban Design and Places Panel and the World Cities Summit Young Leaders Program.