Melbourne’s Public Art: Driving Cultural and Economic Value

Public art isn’t just decoration. It is an investment that delivers measurable cultural, social and economic returns.

Melbourne already hosts projects where art has transformed precinct identity and market appeal, yet the opportunity for developers and policymakers to harness this value is far greater.

At Melbourne Square, Troy Emery’s Guardian Lion, a 15.4m by 18.7m laser-cut aluminium sculpture illuminated with LEDs (picture above by Alpha Juliet Visuals), turns a blank wall into an iconic landmark.

Commissioned by OSK Property, the work is highly visible to thousands of commuters travelling to and from the airport each day, embedding cultural branding directly into the urban fabric.

On the city’s western edge, Jon Campbell’s Backyard (2021) was integrated into the $1.8-billion Western Roads Upgrade. The vibrant, stylised work doesn’t simply decorate infrastructure; it humanises it, becoming an iconic marker and memory trigger for local communities.

At The Alba at Albert Park, the Bunurong Ballart sculpture (picture below by Heath Warwick) was co-created by emerging artist Koorrin Edwards and established artist Dr Treahna Hamm.

The collaboration fostered cultural transfer from one generation of artist to the next, ensuring a continual connection to Country.

Taking the form of a 2m-high bronze basket traditionally used to carry the fruit of the cherry ballart tree, the work symbolises the passing forward of knowledge and stories.

Positioned at the entrance to a residential aged-care complex, it is a fitting gesture in a place where younger family members visit their elders, linking cultural continuity with lived experience.

Meanwhile at Docklands, Mirvac’s Home Docklands project has embedded the Docklands Contemporary Art Collection across public and interior spaces.

Large-scale commissions by Alexander Knox, Jamie North, Meagan Streader, Vipoo Srivilasa and Marta Figueiredo reposition the precinct as a cultural destination while enhancing property appeal.

Victorian creative industries minister Colin Brooks said his government was “proud to back this commissioning program, which has brought incredible art to the Docklands while showcasing the powerful role creativity can play in urban renewal”.

The return on investment in public art is tangible. It manifests in increased foot traffic and dwell time, in a precinct’s ability to differentiate itself, in tourism draw and business activity, and in the resilience of cultural identity over time.

UAP’s Public Art 360 initiative, developed with Griffith University, quantifies these benefits. By tracking visitation, business interest and brand equity, the tool reframes art as a measurable economic and social catalyst.

“Public art is good for business,” director of curatorial at UAP Natasha Smith said.

“It attracts audiences, supports jobs, generates revenue, underpins tourism and spurs development… Public Art 360 seeks to capture those outcomes with evidence.”

The strongest results come when commissioning begins early.

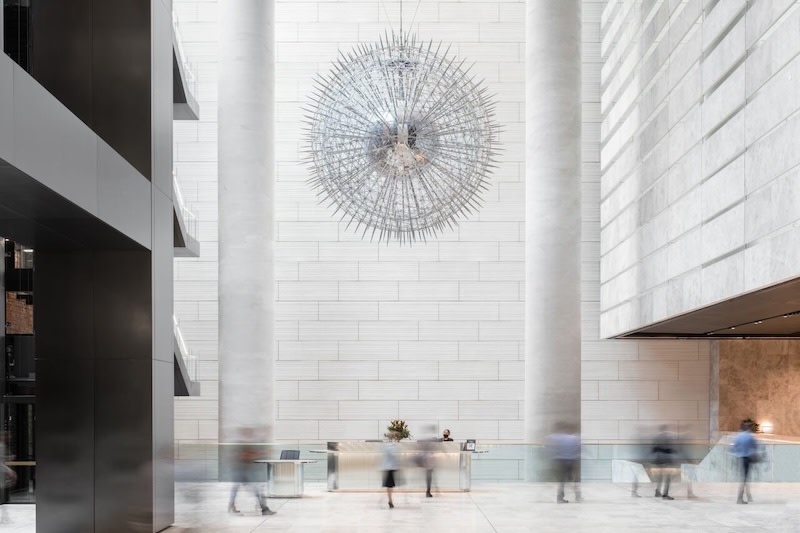

At Olderfleet, UAP worked with Grimshaw, Carr Design Group and Mirvac from the briefing stage to shape a curatorial framework and manage an international design competition.

The outcome demonstrates how early involvement and fabrication expertise produce works that are both contextually relevant and enduring.

For developers, the lesson is clear. Public art is not an accessory; it is a strategic asset.

Projects that embed art strategies from the outset, that partner with experienced consultancies, and that measure outcomes with evidence achieve greater visibility, stronger branding and an enduring legacy.

Artist-led placemaking is infrastructure investment — and it pays real dividends.

Author

Anna Brash

Associate, Curatorial at UAP

The Urban Developer is proud to partner with UAP to deliver this article to you. In doing so, we can continue to publish our daily news, information, insights and opinion to you, our valued readers.