Development margins across Australian capital cities may soon improve after years of pressure as house sale prices keep rising and construction costs stabilise, according to Domain’s latest Price Forecast Report.

The shift creates opportunities for developers, particularly in Melbourne where Domain chief of research and economics Nicola Powell sees the greatest potential after five years of underperformance.

Australian property prices are expected to continue to rise through the 2025-26 financial year, with Sydney leading growth at 7 per cent followed by Melbourne at 6 per cent.

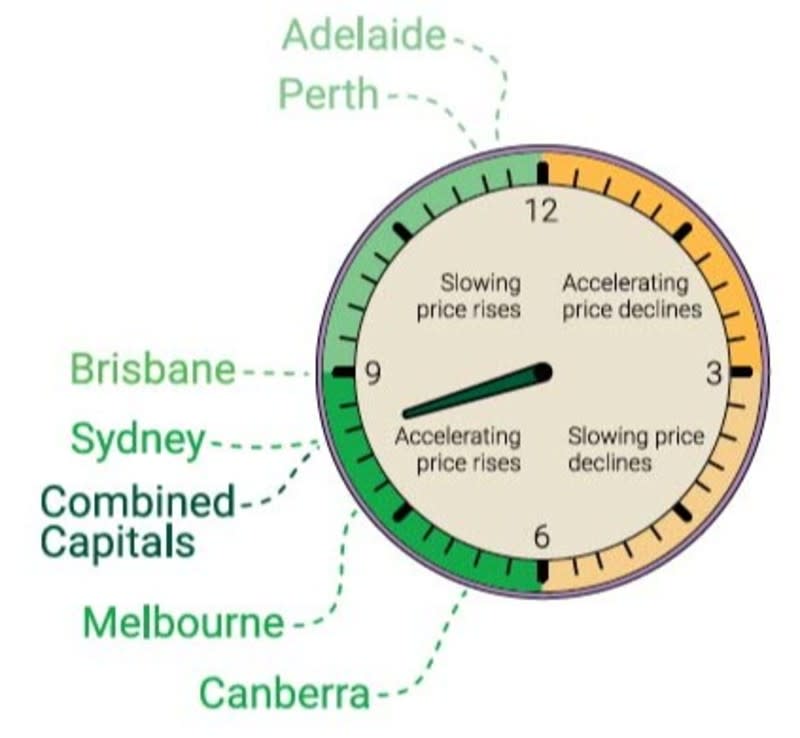

Growth leadership has shifted from smaller, affordability-driven markets to larger, interest rate-sensitive cities, according to the report.

Sydney house prices are projected to reach a record $1.83 million by June of 2026, an increase of about $112,000.

Melbourne house prices are forecast to reach $1.11 million, marking a full recovery from the state’s 2022-24 downturn.

“For developers, and even for lenders, it signals renewed feasibility, and ... upside potential,” Powell told The Urban Developer.

“The increase in demand, particularly in that lender space ... we are going to see higher levels of transactional activity. That plays out positively for developers.

“The baton is passing from affordability driven markets, such as Adelaide, Perth and Brisbane, to interest rates-sensitive markets. And those markets are Sydney and Melbourne.”

Brisbane and Perth, standout performers since 2020, are forecast to experience slower growth as affordability constraints mount.

Brisbane house prices are expected to rise 5 per cent to $1.09 million, while Perth are to grow 5 per cent to $982,000.

Adelaide growth will slow to 4 per cent, reaching $1.05 million.

Powell highlighted Melbourne as offering exceptional value for developers.

“Melbourne is a key callout. It is a major capital city that’s underperformed, and we know that Melbourne is typically valued higher than this—so we expect the market performance to revert to what you would historically expect from a major capital city,” she said.

The price gap between Melbourne and other capitals has also narrowed dramatically.

Five years ago, Brisbane, Adelaide and Perth were 35 to 45 per cent cheaper than Melbourne.

Today, there is just a 1 to 3 per cent variance across these cities, while Sydney has blown out to be 63 per cent more expensive than Melbourne, up from 26 per cent five years ago.

“That undervalued nature of Melbourne and the fact that Victoria by FY27 is forecast to be the fastest-growing state in terms of population growth, which is the biggest driver of demand for housing ... everything points for stronger conditions coming out of Melbourne,” Powell said.

The Reserve Bank has cut rates by 50 basis points since February—markets are pricing additional cuts by mid-2026.

Powell said roughly 100 basis points of cuts translated to $100,000 increased borrowing capacity for average Australian households.

“That’s the difference between somebody being able to purchase a two-bed versus a three-bed or a home better positioned in a more desirable part of a neighbourhood rather than a busy street,” she said.

“That purchasing power is going to diminish in the face of rising prices, but I think that there will be a wave of buyers who will want to purchase before prices rise even further.”

Powell said the pricing gap between new and established properties remained a key constraint.

“We do need to see established prices rise because there is still that gap between the cost of purchasing new versus the cost of purchasing established,” she said.

“You’re not going to see new demand being skewed towards new developments until we see that greater parity between buying established and buying new.”

Affordability challenges represent the primary headwind across markets but also create development opportunities.

Mortgage repayments now account for more than 55 per cent of typical dual-income household earnings in Adelaide, up from 27 per cent in 2019, with Brisbane buyers devoting around 50 per cent of income to mortgage repayments.

These pressures are reshaping demand patterns, with unit markets forecast to grow 5 to 6 per cent versus houses at up to 7 per cent across most capitals.

The biggest demographic increases over the next five years were people in their early 20s and 40s, as well as retirees, driving demand for affordable inner-city options and family-friendly middle suburbs respectively, Powell said.

“East coast markets are regaining momentum, but growth will depend heavily on local factors like affordability and population changes,” she said.

“Lower interest rates, cheaper borrowing, and targeted support for first-home buyers will keep prices rising, especially in Sydney and Melbourne, which are most sensitive to rate changes.”

Despite improving conditions, planning approvals and construction labour remain major bottlenecks limiting supply, with infrastructure projects competing for skilled workers and geopolitical issues creating new risks to development costs.

“If it adds an inflationary pressure due to things like higher petrol prices, it will mean that we won’t see as many cash rate cuts as what is currently being expected,” Powell said.

Powell is not the only one who thinks Melbourne’s development landscape is experiencing renewed confidence as the city shakes off years of underperformance.

Private credit markets are flush with capital seeking opportunities, with MaxCap’s Bill McWilliams saying “there’s more capital that’s flowed into private credit than there are cranes in the sky”.

Combined with stabilising construction costs, improving builder capacity and greater certainty in feasibility planning, industry leaders believe Melbourne is positioned for its next development cycle to begin.